A Highlight of the GEM: Tutankhamun’s Restoration Stela

On November 1, the world celebrated the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum, which more than fulfills the grandeur of its name. Its soaring atrium features a colossus of Ramesses II, and that pharaoh, who ruled nearly seven decades, would undoubtedly be thrilled to be the king that first greets visitors of the GEM. Now, visitors can ascend the dramatically lit Grand Staircase—with its impressive royal statuary, images of gods and kings embodying gods, shrines, columns, stelae, and sarcophagi—to the Main Galleries and the Tutankhamun Gallery. The design of the Main Galleries is inspiring, with three themes—society, kingship, and religion—placed parallel to one another, giving the visitor the opportunity to view the artworks chronologically across themes or to explore each theme from the Predynastic Period through the Roman Era, and then start again with a new theme. The Tutankhamun Hall displays every artifact from KV62—over five thousand of them!

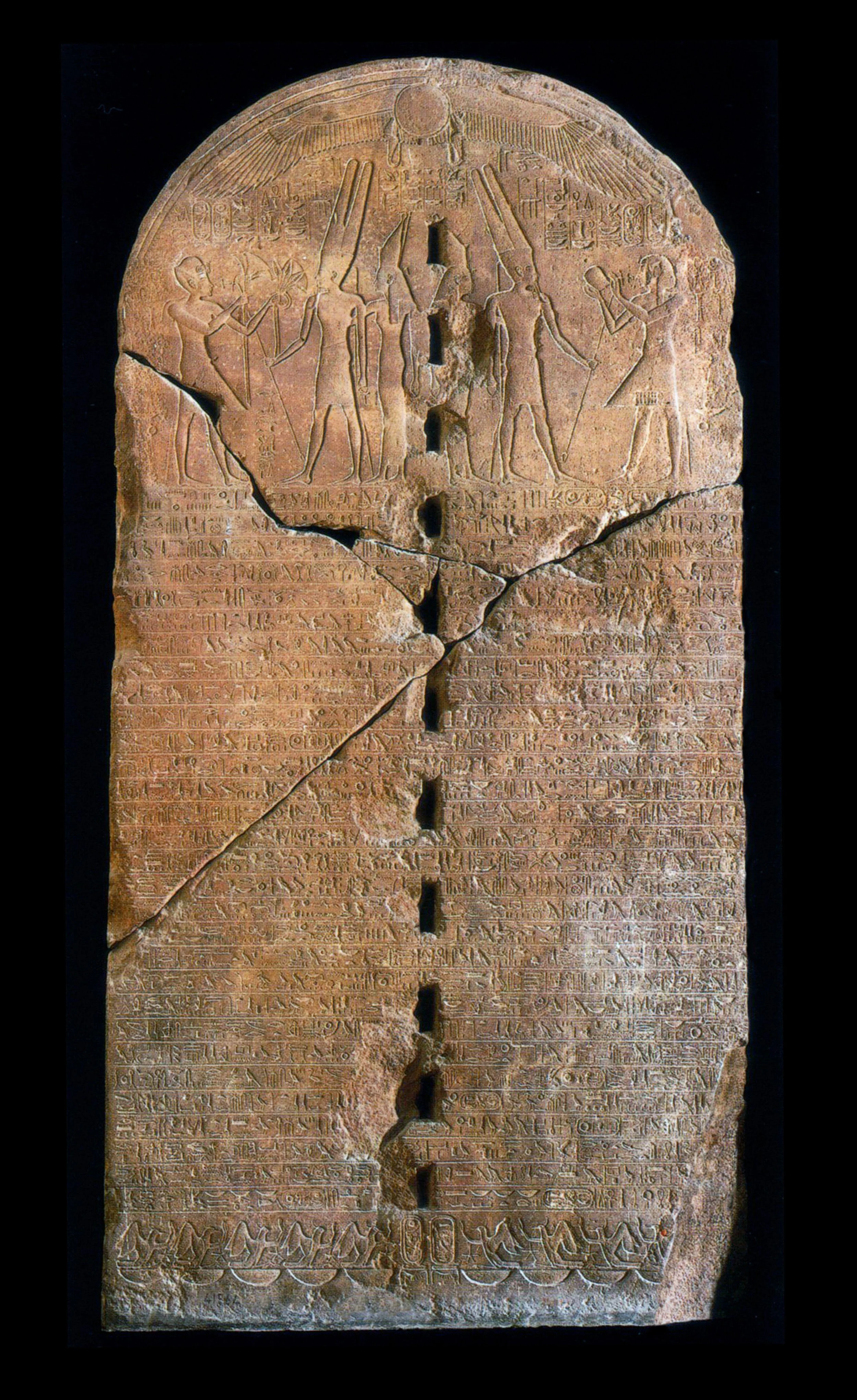

Since we have yet to see the Tutankhamun galleries in all their glory, here we shall describe a unique monument in the Main Gallery that provides an excellent prelude for a visit to the boy-king’s treasure: the so-called Restoration Stela. The impressive round-topped monument was discovered by Georges Legrain in 1907 in the Hypostyle Hall of Karnak Temple. The lunette shows Amun and Mut two times, facing away from the center of the stela and towards King Tutankhamun, who presents bouquets and libations. When the stela was first carved, Ankhesenamun appeared behind her husband—but when Horemhab usurped the entire monument and had his cartouches carved over those of Tutankhamun, the general-turned-pharaoh also eliminated the image of Ankhesenamun.

Restoration Stela of Tutankhamun (CPA Media Pte Ltd / Alamy)

Like all royal monumental texts, one must interpret the text with caution. The Restoration Stela is not intended to present a bare list of events, but specifically to place events and actions within a theological context. The Restoration Stela is what Tutankhamun and his advisors wanted their contemporaries and future readers to know: Tutankhamun is a king who—as expressed succinctly in the text known as The King as Solar Priest— “brings about Maat (cosmic order, justice, truth)” and “destroys Isfet (chaos and immorality).” Royal stelae are important historical documents, but they must be read in a context of royal theology—to dismiss them as “propaganda” is both anachronstic and simplistic.

The following overview of the text of the Restoration Stela is an excerpt from our 2007 book Tutankhamun’s Armies: Battle and Conquest during Ancient Egypt’s Late 18th Dynasty (John Wiley & Sons). The text begins by vilifying the ineffectiveness of Tutankhamun’s father and the deplorable state of Egypt’s temples. Nowhere does the name of Akhenaten appear, and much of the text dwells on the psychological effects of the Amarna revolution—the gods of Egypt no longer hearkened to people’s prayers:

At the time when his Majesty was crowned as king,

the temples of the gods and goddesses,

beginning in Elephantine and ending at the marshes of the Delta [...] had fallen into ruin.

Their shrines had fallen into decay,

turning into mounds and teeming with weeds.

Their sanctuaries were like that which did not exist.

Their domains were foot paths.

Because the gods had abandoned this land, the land was in distress.

If an army was sent to Djahi (the southern Levant), in order to widen the boundaries of Egypt,

they could not succeed.

If one petitioned to god in order take counsel from him,

he could not come at all.

If one prayed to a goddess likewise,

she could not come at all.”

After being crowned Pharaoh, Tutankhamun responds to the Amarna crisis by “taking counsel with his heart, searching out every occasion of excellence, and seeking the effectiveness of his father Amun.” Although the “Restoration Stela” uses phrases found in other Egyptian texts, interesting details enhance the historical accuracy of the report. For example, the stela tells us that when Tutankhamun ponders the problems he inherited from his father, he was living in the palace of “Aakheperkare,” the prenomen of Thutmose I, who ruled almost two hundred years before Tutankhamun. The mention of this specific palace, located near Meidum, provides a real historical setting for the events in the Restoration Stela.

After these deliberations, the Restoration Stela of Tutankhamun then lists the specific endowments he made to divine cults throughout the country. For the god Amun, who bore the brunt of the proscriptions of Akhenaten, and the god Ptah, chief deity of Memphis, Tutankhamun adds to the number of carrying poles used to transport the divine images during religious processions; although not explicit within the text, the increased number of carrying poles also implies larger barks and more priests to man the poles.

Tutankhamun further commanded that new divine statues be made out of the finest electrum and other precious minerals and that new processional barks be constructed out of the best cedar from Lebanon and decorated with gold and silver. During the closure of the temples under Akhenaten, many of these statues and barks may have been stolen or damaged. All of the priests, singers, dancers, and servants of the temples were restored to their former positions and granted a specific decree of royal protection, because by serving the gods, the temple staff was ultimately responsible for the protection of the land of Egypt. The temples also benefited from Tutankhamun’s military success—really, those of his generals—since the stela reports that prisoners of war filled the temples as servants. In sum, the Restoration Stela states that Tutankhamun “has made great all the works of the temples, doubled, tripled, and quadrupled!” The result of Tutankhamun’s restoration program is prosperity at home, military success abroad, and most importantly the return of Egypt’s pantheon:

The gods and the goddesses who are in this land, their hearts were joyful.

The possessors of shrines were rejoicing.

The banks were acclaiming and jubilating, exultation was throughout the entire land.

A great [event] has happened!

The text of the Restoration Stela—discovered fifteen years before the king’s tomb—provides unparalleled insights into one of the most important goals of his kingship. In the hundred years since the discovery of Tutankhamun’s treasure-filled tomb, archaeological discoveries have expanded our understanding of Egypt during his brief reign, including how Egyptian state maintained a strong approach to its desert hinterlands. In March of 1997, members of the modern Egyptian army stationed at an outpost near Kurkur Oasis discovered a stela with a unique text—and John published this amazing monument in 2003. The text underscores the importance of Faras and its extensive network of desert roads during the reign of Tutankhamun and provides a glimpse of the somewhat surprising functions and importance of a modest Nubian patrolman and highlights an otherwise unknown corner of Nubian administration—the frontier secret service.

Behind the glittering gold of Tutankhamun’s mask and the thousands of other treasures of his tomb stands the same administrative complexity, military might, and unifying religious beliefs that underlie so many of the remarkable achievements of ancient Egyptian civilization celebrated in the new Grand Egyptian Museum.